ARIANE HELOISE HUGHES

H0rnyCatholicG1rl

APRIL 13th – MAY 25th 2024

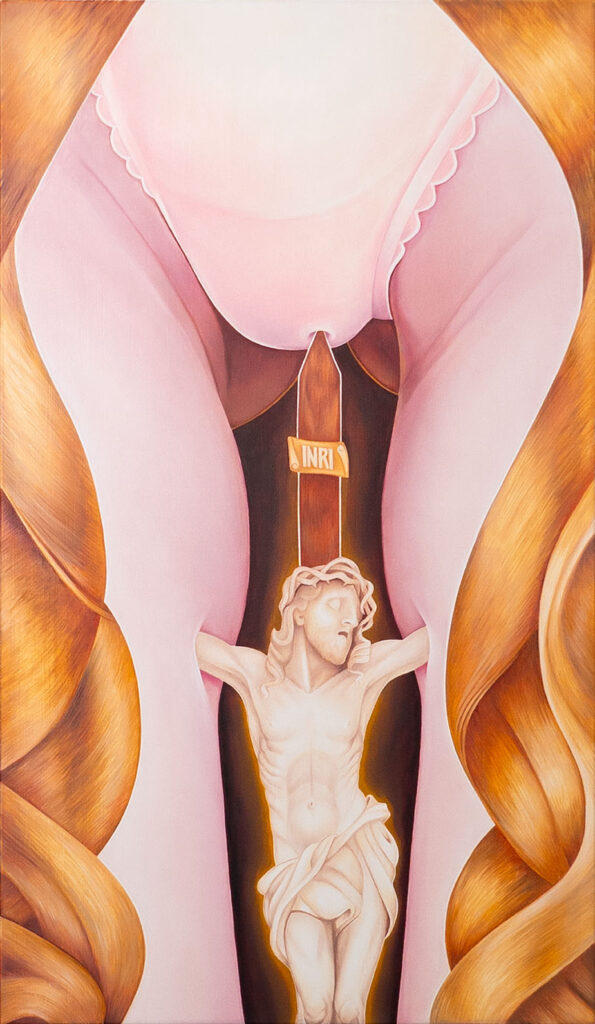

In her work titled “H0rnyCatholicG1rl”, Ariane Heloise Hughes constructs a visual commentary on the perversion of online existence, in which nothing has value, and nothing is private or sacred.

At once surreal, sensual, irreverent, and ironic, she investigates the concept of patriarchy in its various forms and examines the visual codes that continue to influence the images that appear on the web. This can be seen in the wealth of emblems that contemporary women draw on in order to express themselves. Their cultural landscape is detached from the “idols” of traditional Catholic symbolism, embracing a perceived freedom of expression that arises from and is fuelled by the narcissistic phenomenon that is typically found in social media.

Hughes critically dissects these elements, uncovering the notion of a “false freedom”. Despite multiple attempts at emancipation, the filter – or code – that is used to interpret the female figure is consistently shaped by patriarchal intent. This aligns her with writers and critics who adopt a similar theoretical approach. To quote the filmmaker Laura Mulvey:

“In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its phantasy onto the female form, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role, women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness.”

(Laura Mulvey, “Visual And Other Pleasures”)

Similarly, Hughes states:

“I believe that the entire notion of the female gaze is meaningless, for all views are and will continue to be inherently male.”

In contrast to what Lacanians might think, this idea suggests that not even technology would have the power to bring about a sort of “eclipse” of the patriarchy. On the contrary, it would be a subtle reformulation of the previous power which, by promising the illusion of unfettered female manifestation, actually confirms its own dominion.

The idea is that, today, a woman who shares a picture of herself on Instagram only has the illusion of being “empowered”, for this ultimately entails seeking social – and specifically male – approval. This may bring gratification and point to success (in the form of likes, views, and so on), but she is forced to define herself (the ego-related dimension of narcissism) by the standards of what Julia Kristeva refers to as the “I/Not I” dichotomy.

The consumerism of images serves as a deceptive pretext for once again reinforcing the control of the patriarchy. The web takes the place of God – Hughes says that “with the decline in religion we are inherently lost” — but in actual fact, the way women view themselves remains unchanged.

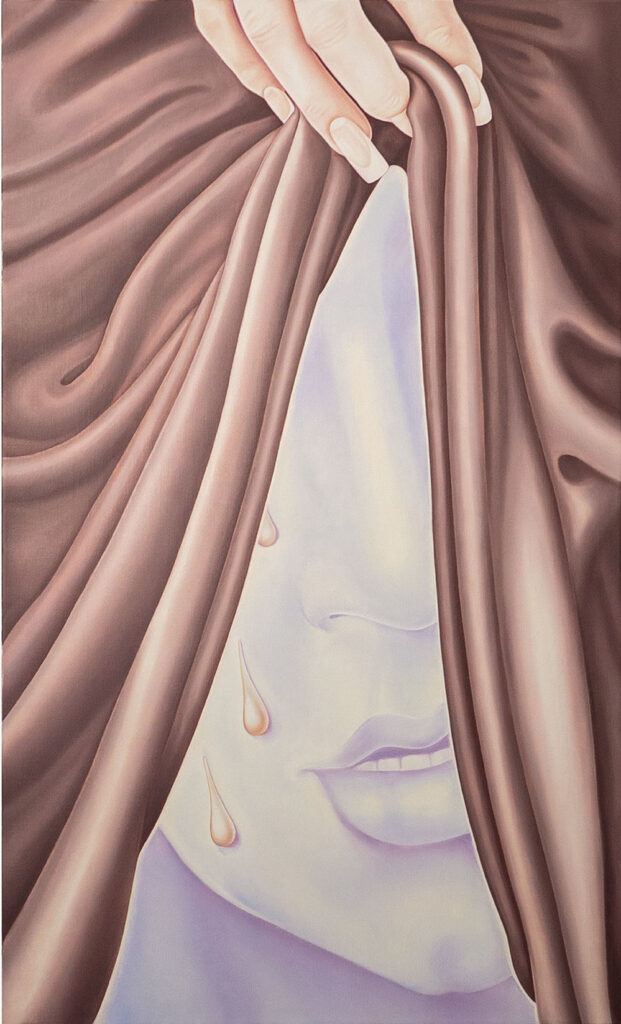

On the one hand, Hughes becomes a “witness of impotence”, and yet on the other she offers a clear sardonic nod to the viewer with regard to the contemporary world. A world in which online platforms replace yesterday’s altars, creating pseudo-oracles that draw the user into a form of progressive isolation. This is brought about and manipulated by means of a screen that both “masks” and “reveals” us.

The display diminishes our senses, and particularly that of touch, in favour of visual hyper-enhancement, promoting the powerful exhibitionist image of the selfie at the expense of our more fragile and intimate domains:

“The horny girl part is a childish infantile immature never-ending struggle of wanting to be desired and seen in the digital age without the ability to (the fear of even?) actually be perceived or tangibly understood.”

New symbols such as hairstyles, long painted nails, and nude bodies exposed to voyeurs, overlap with the clerical imagery of a young woman of the new millennium. A woman heroically grappling with self-(re)discovery within the paradoxes of the venerable and the profane, of self-awareness and social complexity.